For decades, many artists from the former Royal Academy of Performing Arts (RAPA) have faced an abrupt career crossroads at 40. Under existing rules, they are required to retire from the institute at that age. With most having only a Class 12 education, transitioning into new professions has been a struggle, leaving many unsure of their future.

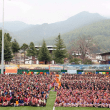

Today, that narrative took a hopeful turn. The Royal Institute of Performing Arts (RIPA) was officially inaugurated in Thimphu, welcoming its first batch of 10 students into a Diploma in Performing Arts programme. The initiative is designed to both safeguard Bhutan’s living cultural heritage and give future performers the skills and qualifications to thrive beyond the stage.

Bhutan’s performing arts — from the sacred rhythm of mask dances to the plaintive strings of the dramnyen and the harmonies of folk songs — face mounting threats. A shortage of trained performers, coupled with the mandatory retirement of seasoned artists, has thinned the ranks. Without a dedicated training institution, the tradition’s survival has grown increasingly fragile.

The two-year diploma will cover mask dances, Bhutanese theatre, traditional instruments such as the dramnyen and yangchen, cultural studies, and live performance opportunities at national events. Graduates will initially serve as artists with the newly renamed Traditional Performing Arts and Music Division, RAPA’s successor, until the age of 40. However, the programme is also designed to equip them for broader opportunities, from teaching to cultural consultancy.

“The artists we have today are incredibly skilled, but when it’s time to move on, they lack the certification needed to secure other jobs,” said Phub Wangdi, Officiating Principal of RIPA. “This programme ensures that won’t be the case for future generations.”

For the new students, the opening marks the start of long-awaited dreams. “As youth, it’s our responsibility to safeguard our culture,” said Pelzin Dema, one of the first enrollees. “I’m most excited about the chance to one day teach music in schools.”

Tenzin Dorji, who had been idle since finishing Class 12 two years ago, described the programme as a lifeline: “Ever since I was a child, I wanted to sing and play instruments. Now I finally have the chance to learn professionally.”

By 2027, RIPA aims to graduate at least 50 professionally trained artists, strengthening Bhutan’s cultural identity, inspiring young people to engage in heritage preservation, and elevating the country’s presence on the international cultural stage.

In a nation where tradition is both a living art and a fragile treasure, the new institute may prove to be not just a school, but a safeguard for the soul of Bhutan.