For more than two millennia, the Buddha’s teaching has rested on a delicate balance: the fourfold assembly of laymen, laywomen, monks, and nuns. If any one of these pillars disappears, the Dharma itself is said to fade. While male ordination lineages remained largely intact across Buddhist Asia, the full ordination of women—bhikshuni or gelongma—vanished in many regions, becoming rare, fragile, and fiercely debated.

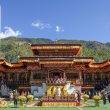

In November 2025, a historic turning point arrived in Bhutan. Over five days, 265 women from 14 countries received full gelongma ordination in the Mulasarvastivada tradition, restoring a lineage long believed to be irretrievably broken in Himalayan Buddhism. The ceremony, presided over by Ngawang Jigme Chhoeda, marked the largest such ordination in this tradition’s history—and a powerful affirmation that women belong fully within the heart of the Sangha.

For centuries, many Himalayan nuns were taught that the highest monastic vows were unattainable in this lifetime. Some quietly prayed to be reborn as men so they could one day receive full ordination. Others were told that alternative paths to awakening were “sufficient,” even if unequal. Yet scholarship over recent decades has demonstrated that, according to early Vinaya sources, monks possess the authority to ordain nuns even in the absence of an existing bhikshuni community—precisely how ordination occurred during the Buddha’s lifetime.

Those findings slowly shifted the conversation from ideology to evidence. The result has been a cautious but steady movement toward revival, often supported by senior monks, Vinaya scholars, and increasingly by Buddhist communities themselves.

In Bhutan, that momentum found courageous leadership. Despite early objections and appeals against the initiative, the Je Khenpo declared that reviving gelongma ordination was both correct and timely. The Bhutan Nuns Foundation, under the guidance of Dr. Tashi Zangmo and with the patronage of the Queen Mother, undertook the immense task of organizing an international ceremony that combined ritual precision, logistical care, and spiritual vision.

For many of the new gelongmas, the experience felt almost unreal. Gelongma Chojay Wangmo, a Bhutanese nun who had once doubted whether she should even apply, described feeling “truly blessed to be part of the authentic sangha.” Her ordination, she said, was not only a personal milestone but a commitment to serve society—as educator, social worker, and role model.

Tibetan nun Gelongma Rigzin Dolma traveled with 52 sisters from her nunnery to attend. She recalls tears of joy when receiving her vows, and a deep sense of continuity with ancient practitioners: “It felt as if we had all reached the times of our ancestors.”

Perhaps the most visible symbol of that continuity came on the final day, when the newly ordained nuns walked barefoot on alms round through the streets of Thimphu. Thousands of people lined the route, offering food with reverence. The King and Queen were among the first to give alms—an unprecedented public recognition of women as fully ordained monastics.

Western nuns also participated, some after decades of waiting. Gelongma Ngawang D. Dolma described three dominant feelings: completeness, deep gratitude, and responsibility. “I finally felt like a complete nun,” she said. “Now we must become examples for the younger generations.”

That sense of responsibility echoes throughout the community. Reviving a lineage is only the first step; sustaining it requires continuous Vinaya education, mentorship, regular rains retreats, and institutional support. The Bhutan Nuns Foundation envisions a future training and research center where nuns from around the world can study and practice together—ensuring that this once-lost lineage never again fades into obscurity.

The November ordination was not merely a ceremonial success. It was a quiet revolution, carried out in the conservative, patient manner characteristic of Buddhist institutions: slow, careful, and ultimately transformative.

As one nun reflected, progress does not come from removing every thorn on the path, but from putting on sturdy sandals and walking forward. In Bhutan, hundreds of women have now taken those first firm steps—walking not only for themselves, but for countless future generations who will know, without question, that the full path of monastic life is open to them.