A recent national survey has uncovered a troubling source of toxic exposure for Bhutan’s children: the very toys and household items that fill their lives. The 2024 National Blood Lead Level Survey revealed that nearly one in four playthings tested in schools and Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) centres contained detectable lead, with roughly 9 percent exceeding safe limits.

Until now, many childcare professionals believed that lead poisoning in Bhutan stemmed primarily from environmental sources such as old paint or contaminated soil. But the survey—conducted across six schools and four ECCD centres—identified lead in 23 percent of 209 items, and above-threshold levels in about 9 percent of both general and commercially manufactured toys for children over the age of one. Health experts warn that even minimal lead exposure can impair cognitive development, stunt growth, and damage neurological systems.

“This finding was a wake‑up call,” said 34‑year‑old Dhan Maya Rai, an ECCD facilitator with nearly a decade of experience. “I had no idea that the everyday objects we provide our children could be a source of lead.” In response, Rai and her colleagues have begun integrating rigorous hand‑ and toy‑washing routines into their centres. They are also collaborating with parents to craft simple wooden toys locally, reducing reliance on brightly colored plastic or metal items whose composition may be unknown.

To make these shifts stick, ECCD centres are deploying a mix of songs, stories, and pictorial workshops to educate both children and their caregivers about healthy hygiene habits and the dangers of lead exposure.

Physicians at Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital echo these preventive steps. “If toys are the culprit, the ideal approach is to select certified products with verified low lead content,” said Dr. Tulsi Ram Sharma, a paediatrician at JDWNRH. He recommends daily cleaning of play areas—mopping floors, wiping down railings, and washing toys—to minimize the risk of ingestion or inhalation of lead particulates.

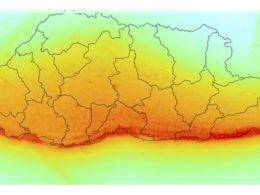

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health has made lead prevention a cornerstone of its ECCD outreach. “We have trained and sensitized facilitators across six western dzongkhags on children’s environmental health, with a focus on lead poisoning prevention,” explained Karma Wangdi, a programme analyst with the ministry. “We are also building capacity among frontline healthcare workers to carry these messages into the community.”

While awareness is rising, Bhutan faces logistical hurdles. Certified low‑lead toys can be scarce and costly in rural areas, and local production of safe alternatives is still nascent. Yet, with coordinated efforts from ECCD centres, health authorities, and families, Bhutan is charting a course to protect its children from this invisible threat.

As the nation digests the survey’s findings, the shared goal is clear: transform knowledge into action, so that children can play freely—without compromising their health or future.